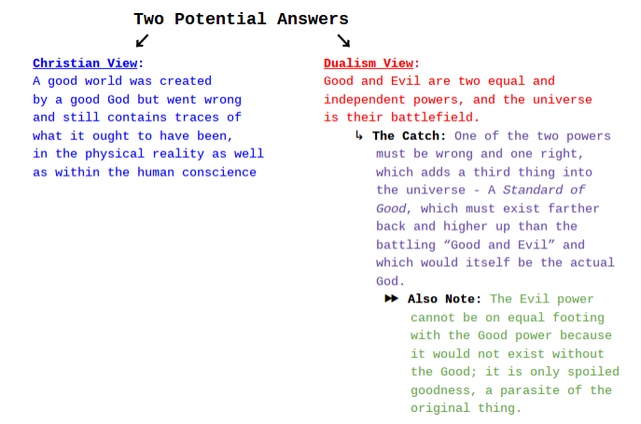

- We deny that this God even exists and convince ourselves it is all nonsense and fairy tale, so there really is no threat to our Pride at all.

< OR > - We turn this God into something that can be beaten, something that is much more suitable to our Pride and much easier to compete against.

Pride is so dangerous because we are usually unaware of its presence, and it is often used to cure our other evils; we overcome some vices by learning to see them as beneath our dignity. So we become self-controlled and wise and courageous, while all along we fan the flames of self-conceit. And Lewis says this is all perfectly fine and pleasing to the devil because he would much rather see us fall prey to the cancer of Pride than the ulcer of lust.

- "Pleasure in being praised is not Pride." Finding delight in the compliments or praises of others is a good thing so long as the delight comes not from what you are but from the fact that you were able to please another person (or even God). "The trouble begins when you pass from thinking, 'I have pleased him; all is well,' to thinking, 'What a fine person I must be to have done it.'"

- Being 'proud of' something, like one's child or one's achievements, is not Pride so long as we are using the term to refer to a warm-hearted admiration or happiness we may feel. But it moves toward Pride when we allow those things to puff us up and make us think more of ourselves than we ought.

- Pride is not forbidden by God because it offends Him but because it separates us from Him...

- And finally, on the topic of humility, a humble person is not one who walks around with his head hung low, telling everyone what a nobody he is. When we really find ourselves in the presence of a humble person, we will probably find that "he will not be thinking about humility; he will not be thinking about himself at all."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed