- "We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be." Looking at the present state of humanity, it seems pretty clear that we are on the wrong road, making a mistake. The best way to undo a mistake is to go back to the beginning and rework the problem. If you are taking a trip and find yourself on the wrong road, the most "progressive" solution is not to continue going in the wrong direction but rather to turn back and figure out where you went wrong so that you can get to your intended destination.

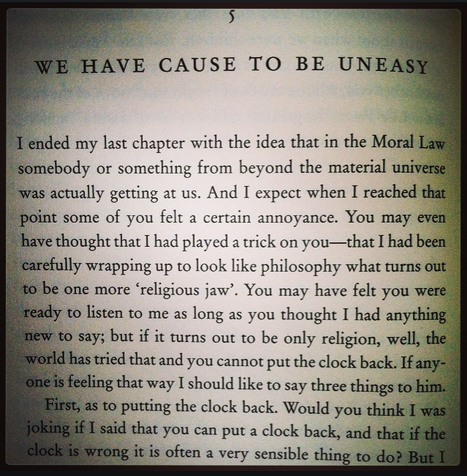

- "We have not yet got as far as the God of any actual religion, still less the God of that particular religion called Christianity." We have only gone far enough to say that there is Someone or Something who created the Moral Law, and we only really have two clues as to what this Someone is like:

A. The universe he has created indicates he is a "great artist (for the universe is a very beautiful place) but also that He is quite merciless and no friend to man (for the universe is a very dangerous and terrifying place)."

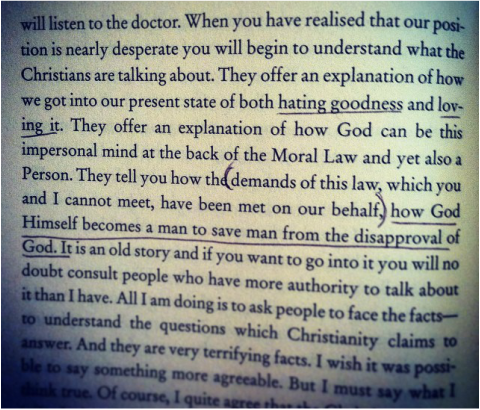

B. The Moral Law he has put into our minds indicates that he is intensely interested in right conduct, but not in an indulgent or sympathetic way because there is nothing soft about the law of morality. "If it is pure impersonal mind, there may be no sense in asking it to make allowances for you or let you off, just as there is no sense in asking the multiplication table to let you off when you do your sums wrong." - "Christianity simply does not make sense until you have faced the sort of facts I have been describing." The Moral Law reveals the weakness of humanity and our tendency toward immorality, toward selfishness and deceit and manipulation and hatefulness and pride, breaking the very laws of morality we feel everyone else should be keeping. Christianity offers answers to the questions that arise from the dilemma of the Moral Law and the Power behind it, but the Moral Law also underscores our need for the answers that are offered by Christianity.

In the end, Lewis acknowledges that the potential reality of Christianity, or even of just a Divine Creator/Intelligence, may be discomforting for many, but he concludes that we could never gain comfort by looking for comfort. Instead, he says, look for Truth and you may also find comfort along with it. "If you look for comfort you will not get either comfort or truth - only soft soap and wishful thinking to begin with and, in the end, despair."

How has our culture been seemingly successful at creating the illusion that Christianity and logical, rational, scientific Truth are at odds with one another?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed